by Cherrie Kandie

Cherrie Kandie’s reflections on African grandmothers and network weaving is part of Network Weaver’s BIPOC Editorial series. Learn more about the series and our submissions guidelines here. We invite you to connect with us at [email protected]

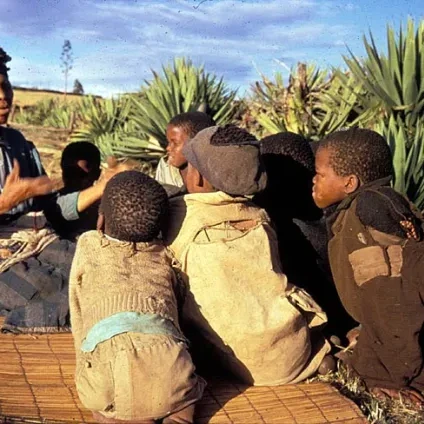

In many places around the world, the elderly are considered a burden. Many are placed in care homes away from their families and communities. Care homes aren’t necessarily a bad thing, but I’d like to offer a perspective about how invaluable grandmothers are in the rural Kenyan indigenous community I live in.

A few months ago, my grandmother fell sick. I spent nights with her in the hospital, sleeping on the floor and helping her eat and bathe in the mornings. I’d walk home to hand wash the clothes she’d worn before sleeping during the day then going back to the hospital in the evening. Sometimes, I carried my laptop to work through the night.

Gartner, the information technology company, partially defines a social technology as: “Any technology that facilitates social interactions.” For example, my laptop is a social technology because it allows me to work and make connections with people from all around the world. One day, while working on my laptop and looking over my grandmother in her hospital bed, I realized that grandmotherhood was a social technology too. Her weakened body mobilized everybody to care for her. I saw that old age made her more valuable to my community where in other contexts it would have been a burden. In her moments of sickness, my grandmother functioned as a node of healing, transmission, and connection.

As my grandmother received tons of visitors and got many calls, she told each person that I was taking care of her. I felt valued by all the people who loved her, which in turn made me commit even more to her care. They gave me gifts and words of encouragement. It was as though the love she’d given to them throughout their lives was coming back to me through the care I was giving her. I got to meet many people I wouldn’t have met otherwise. And for those who spoke with my grandmother on the phone but didn’t meet me, my name remained in their minds as a caregiving child who deserved goodwill and blessings.

My mother told me that it was special that the child of her child (mokochoret) was taking care of her, and that’s why she wanted everybody to know. The extraordinary breadth of my grandmother’s life was contained in the fact that her body had nurtured a child, who had then nurtured another child, who had now returned to care for her body at its weakest. A perfect circle. She wanted everybody to know how much she was loved. In this context, being loved by other people is a form of success.

No matter how cold or bleary-eyed I got during those nights, it never once crossed my mind that my grandmother was a burden, mainly because of how my grandmother’s wide network of friends and family had supported both of us. One morning, because I was so tired, I sat by the river that ran near the hospital. I had whimsical hallucinatory thoughts about time and space and the stars. My physical exhaustion hadn’t weakened my spirit. Rather, my exhaustion had pushed open certain doors, like a purging. Those amazing thoughts wouldn’t have been possible if I wasn’t so tired within the context of caregiving, and those philosophical breakthroughs prepared me for the next stage of my life as a writer and human being.

Walking home that morning after sitting by the river, I stopped to marvel at the perfection of an enormous sunflower that was about my height. I began to cry. Before my grandmother had fallen sick, I had struggled with terrible doubts about the world and my place in it. The pain, dying, and suffering around me had felt overwhelming, not to mention people’s myopia and selfishness. But then I felt that the sunflower’s messy beauty had demanded, “Look at me!” Then when I looked closer, the mathematical perfection of the spirals at the heart of the flowerhead had told me to be still, because things would come together at the end. And they did.

Cherrie Kandie

African grandmothers are network weavers and social technologies. Old age makes them more valuable to their communities where in other contexts old age would make them a burden. I currently live within these communities and they’ve healed a lot of my pain and hangups, with grandmothers functioning as nodes of healing, transmission, and connection, even as their bodies weaken and I am mandated to take care of them.

featured image found at Canva

Network Weaver is dedicated to offering free content to all – in support of equity, justice and transformation for all.

We appreciate your support!