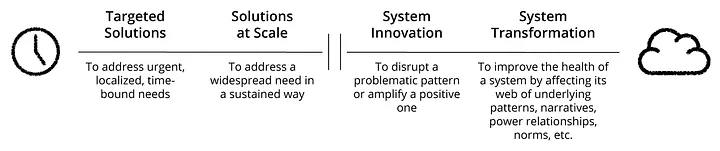

The Complexity Spectrum blog describes how clock and cloud (non-system change and system change) approaches require fundamentally different strategies and tactics. The same goes for the mental models and processes we use to govern system change work.

In fact, governance for system change may not look much like traditional governance at all. Webster’s defines governance as “overseeing the control or direction of something.” Because system change work is emergent, long term and comprised of dispersed and diverse actors, centralized control and oversight is unworkable if not impossible.

Rather, system change work requires distributed decision making in pursuit of a common aspiration and in response to emergent facts on the ground. While centralized control may be impossible, there are ways to bring coherence to this work, increasing the probability of shifting a system to a more desired state.

In this case, governance applies to anyone who makes important decisions that affect the probability of success of a collective system change endeavor, and not just to members of a board of directors.[1] This type of governance is difficult and often requires building a range of new practices over time. Here are a few practices that may help:

- Capitalize on uncertainty to lower risk and increase chances for success.

- Focus on creating the conditions for change over short-term outcomes.

- Liberate choice rather than trying to control it.

- Rely on multiple ways of knowing as you navigate the journey.

Practice #1: Capitalize on Uncertainty

“Uncertainty is an uncomfortable position. But certainty is an absurd one.” -Voltaire

Depending on where you engage on the Complexity Spectrum, uncertainty can be a problem or it can provide a valuable opportunity.

Targeted solutions require a technical approach where you move efficiently along a mostly known pathway from a known problem to a known solution. Take for example a population that has been displaced by a natural disaster. We have experience dealing with this type of situation (known problem) and delivering the targeted solution of emergency shelter (known solution) though various tried and true means (mostly known pathway). In this case, uncertainty can be disruptive because it creates barriers between the problem and the solution.

Solutions at scale usually require an adaptive approach (think Human-Centered Design).

For example, in California many more people were eligible for benefits to alleviate poverty and food insecurity than were applying for them. The reasons why the problem existed were fairly well understood (sufficiently defined problem). In response, Code for America talked to people to understand why they weren’t applying and how they could provide a solution. They built an app, iterated it, and eventually launched a product (GetCalFresh) that greatly increased the number of eligible people applying for benefits (iterated to find a solution that was initially unknown).

An adaptive approach requires a fair level of certainty about the definition of the problem and its causes — enough to support a process of managed uncertainty in which you experiment to find deeper causes and solutions to the problem.

System transformation calls for an emergent approach.[2] In an emergent approach, while you are likely certain about the negative symptoms of the challenge (e.g., high levels of poverty or inequality), the deeper drivers of the problem and reasons for its persistence are mostly unknown or misunderstood. Consequently, the ways to address these drivers are also mostly unknown (or unformed). The key is to nurture the conditions that will support the system healing itself (e.g., understanding the systemic drivers of the challenge and supporting the emergence of ways to address them).

In an emergent approach, uncertainty unlocks opportunity. When complex challenges persist over time despite efforts to address them, there is often a sense of frustration, even despair. However, this can lead to the realization that we don’t have all the answers, which can make us more open to thinking differently.

Some forms of systemic analysis, like dynamic system mapping or participatory futures, provide a structured process for thinking in new ways about an all-too-familiar problem. When doing participatory system mapping, aha moments often arise when participants identify a pattern that explains why change has been elusive. It is empowering to see an old problem from a different perspective and find a possible path forward.

Effective system sensing should lead to confidence that you have “good uncertainty” — or trust that there are good questions to explore and a way to experiment and learn more about the system and how to engage it. Think of uncertainty as a gateway to doing things differently and finding ways to unstick a stuck system.

Practice #2: Focus on Creating the Conditions for Change

Uncertainty is uncomfortable because it increases our fear of failure. It makes us anxious. One common but ultimately unhelpful response is to over-rely on short-term substantive outcomes that are a small piece of the ultimate outcome we want to see. [3] For example, if we are looking to end human slavery in global supply chains, we might measure progress by looking for annual percentage reductions in the estimates of slave labor by 5% or so each year.

It is wise to understand the impacts our work is having in the short term, if for no other reason than to detect and mitigate potential negative impacts. However, there is a danger of using pre-defined, substantive outcomes as waypoints to navigate our way on the journey toward long-term system change.

Specifically, there are two key dangers:

- Short-term outcomes dominate our time, attention, and resources and reduce commitment to long-term change. According to neuroscientist Ian Robertson, “success and failure shapes us more powerfully than genetics and drugs.” This means short-term successes can lead people to invest more time, resources, and emotional commitment in concrete short-term outcomes instead of longer-term, hazier systemic shifts. Moreover, grantees often need to trade annual impacts for continued funding, so pre-identified short-term outcomes take priority.

- Short-term impacts can be bad predictors of long-term, systemic impact. In complex systems, impact is not static. What may seem like a good outcome in the near term, might drive negative downstream impacts in the months and years ahead. Basing future investments mostly on short-term outcomes can lead to bad long-term investments.

The implication is an inexorable pull away from making the hard choices and risk tolerance needed for system change. As a result, the pursuit of specific substantive outcomes in the short term may make it more likely a system change effort fails in the long term.

Fortunately there is an alternative. Alice Evans, who in her time at Lankelly Chase helped build their systems practice, said a key enabler of their work was the realization that creating the conditions for system change should be their focus rather than targeting specific outcomes those conditions might produce.

For example, there are a few generic conditions that will apply, in some form, to most system change initiatives. These include the degree to which important system actors can:

- See their context as a complex system and use that shared understanding to inform action and increase the potential coherence of distributed action.

- Identify and engage patterns that people believe will unlock change (e.g., weakening patterns that sustain the problem or strengthen bright spots that can shift the system).

- Build or strengthen connections, networks, and information flows across the system.

- Build an infrastructure for learning and, as Marilyn Darling says, “return that learning to the system.”

Elaborating these and other conditions that might support system change requires a participatory process that prioritizes the voices of those closest to the day-to-day operations of the system.

As we look at the conditions we are trying to cultivate, we must also look at those in ourselves and in our organizations. We are all part of the respective systems we are engaging and it’s critical to contend with power and who is making decisions both within an organization and in a broader system impacted by those decisions. If you haven’t already done work on your own relationship to power and how it impacts your work, now might be a great time to dig in. Consider asking:

- How are we showing up in the system? What feedback are we getting about how we’re showing up? Are we working in a system-informed way? How do others experience our presence?

- What is the quality of our relationships with other key system actors? How have we prioritized the voices of those closest to the context?

- How do we understand our own power in the context we are working in and the people we are working with? How do others perceive it? How can we engage others in an honest conversation about our relative power?

Fortunately, changing how we show up in a system shifting initiative is a condition over which we have the greatest control. Unfortunately, many of us, especially funders, show up in ways that replicate or entrench unhelpful power dynamics that constrain choice and make distributed decision making impossible. This means a critical early condition for system change is understanding and adapting the ways in which our organizations — and even ourselves — work. For more thoughts on internal organizational conditions and how to work toward them, see Building Emergent Organizations.

Practice #3: Liberate Choice

Successful system change requires those closest to the day-to-day operations of the system to be highly adaptive over time in response to emerging realities.[4] However, this is hard to do with traditional governance processes that seek to maximize control and minimize risk.

For example, a standard grant agreement trades funds for outcomes identified by the donor, which replicates the power dynamic of “those with resources call the tune.” This dynamic too often prioritizes donor interests rather than those most impacted by the funding, removes agency from those closest to the context, and creates highly transactional relationships.

If funders behave in ways that reduce the agency of these actors, they inhibit their ability to work for system change.

The alternative to donors limiting choice is to use what Cyndi Suarez calls “liberatory power,” or the ability to “create what we want” by transforming “what one currently perceives as a limitation.”[5] A key question for donors wishing to support system change is, how can we increase the ability of key actors in the system to effectively connect with each other, sense, sense-make, act on, and learn from their system?

Each level of actor in a system change initiative can liberate the choices of actors in the system. Liberating choice is not the same as giving more choices — it requires both the presence of choice and the agency to act on it. A board of directors needs to liberate choice for organizations they oversee; leadership of an organization needs to liberate choice of its program teams; program teams need to liberate choice of grantees and partners; grantees and partners need to liberate choice of stakeholders and community actors; and based on how information flows in the system, stakeholders can liberate choice for program teams, etc.

This is not the same as simply giving money and getting out of the way. Liberating choice does not mean removing all structure. Many argue there is no such thing as structurelessness when it comes to any kind of group activity, especially when one actor is providing significant resources to support the work of other actors.[6] Donors need to provide enough structure to enable choice, but not so much as to prematurely curtail choice.

The key is to create minimally sufficient, helpful structure. For donors supporting system change, there are some key components to creating minimal structure, which include:

- Articulate a common aspiration or guiding star.[7]

- Clarify boundaries by articulating key interests and values.

- Establish an infrastructure for learning.

- Invest time in building trusting relationships among system actors.

Of these four points, clarifying boundaries or guardrails may be the most difficult. An unhelpful but familiar way of doing so is to provide directives to either do or not do something. A more useful approach is the “even-over statement” as developed by Tom Thomison and popularized by Aaron Dignan.

The benefit of even-over statements is that they share how different actors in the system might make tradeoffs between key interests and values. The statement consists of two “good things” and says, “if confronted with a choice, I would choose this good thing over that good thing.” However, it aims to preserve the agency of an actor to make a decision in light of the specific situations that they find themselves in.

Some generic even-over statements that liberate choice for system change include:

- Prioritize responsible, smaller experiments even over concentrating resources on large-scale bets.

- Invest time in building trusting relationships even over delivering on preset timelines.

- Value responsible learning even over clear-cut wins.

- Foster regular, honest feedback across the network of actors even over preserving harmonious relations.

Whatever boundaries you try to set, and however you set them, they will be wrong in some respect. This is where a dynamic learning process is essential. Part of that learning process needs to ask to what degree are the boundaries and common aspiration helpful? In what ways are they affecting people’s thinking and behavior? Are they strengthening agency of system actors or reducing it? What might we do better?

And none of this works if the relationships between actors in a system change initiative are mainly transactional. Because system change work is highly emergent, it requires real time and honest communication and the ability to work in a decentralized way. All of this requires high levels of trust between actors, and this level of trust does not happen unless they invest time in it. This can be particularly difficult for funders who see investing time to build trust as simply increasing overhead.

Practice #4: Rely on Multiple Ways of Knowing

“There is a strong bias in the U.S. dominant culture, one that shows up in the nonprofit sector as well, to value only one way of knowing, the one grounded in data, analysis, logic, and theory — a rationalist’s approach to truth.” -Elissa Sloane Perry and Aja Couchois [8]

Working effectively in complex systems requires strengthening our ability to use multiple ways of knowing. It is essential for implementing the practices described above. Unfortunately, as the quote from Elissa Sloane Perry and Aja Couchois indicates, the default capacity for many in the West is to privilege only one way of knowing — a cognitive, analytic approach.

This is not to say we should devalue rational analysis. Rather, it means putting a high value on the ways others understand their world and make decisions about how to act.

There are various ways to define multiple ways of knowing, from Howard Gardner’s theory of multiple intelligences to the model of five minds described by Tyson Yunkaporta.[9] A simple way to look at multiple ways of knowing is: thinking, feeling, and intuiting.[10] At a minimum, it means asking: what do you think about the situation, how does it make you feel, and what is your gut telling you to do? It means listening to how others think, feel, and intuit.

Listening to feelings and intuitions is not the same as following them. Rather, it means understanding how information, situations, and decisions make us and others feel; allowing our intuitions to come to the surface; and not automatically subjugating these to what we might judge as rational or rigorous analysis. It means sitting with differences and uncertainty and valuing the important stories people tell about their system, and not just the numbers they can fit on a spreadsheet.

For many, this is the most disruptive practice for system change governance. It requires us to change how we think about and develop strategy, how we evaluate our effectiveness and that of our grantees, and how we make decisions. It means that good questions are often more useful than seemingly good answers. Fundamentally, it changes how we know what we know (e.g., how we weigh a quantitative analysis versus the lived experiences of partners on the ground).

But as disruptive as it can be, cultivating multiple ways of knowing is worth it. There are several reasons why: from the neuroscience that shows the role of emotions in decision making to the necessity of multiple ways of knowing for advancing equity.

In addition, there are simple, practical arguments for cultivating multiple ways of knowing from a system change perspective:

- If shifting systems involves diverse actors spread across geographies and cultures, different ways of knowing will always exist in the network. This means effective system change work requires the ability to understand and work with those different ways of knowing.

- And, because complex systems are murky and constantly changing, it is naïve to rely on only one way of knowing. Each way of knowing has limits but, together, multiple ways of knowing increase our effectiveness.

- Lastly, multiple ways of knowing are essential because we can’t just reason our way to system change — rather it requires a dynamic connection between head, heart, and gut.

One accessible way to start bringing multiple ways of knowing into your work is to play with meeting structure. Try starting meetings with a check-in question like “how are thinking and feeling coming into the meeting?” Or you could ask something more playful like “what was your favorite movie character as a kid?” A more serious question could be “can you describe a time when you felt truly happy?” Think of it less as an icebreaker and more of a space for people to welcome in their whole selves and deepen relationships. It also helps to build in time for silent reflection in the room, have people journal, or to pair up and process the meeting while taking a walk.

Many people have built more in-depth ways to incorporate multiple ways of knowing. A few I suggest are: the Equitable Evaluation Initiative, for using multiple ways of knowing to build more equitable evaluation processes; Relational Systems Thinking: That’s How Change Is Going to Come, from Our Earth Mother by Melanie Goodchild, for how to realize the benefit of differing world views and ways of knowing; and Theory U by Otto Scharmer, for a comprehensive approach to system change that has multiple ways of knowing at its core.

Next Steps

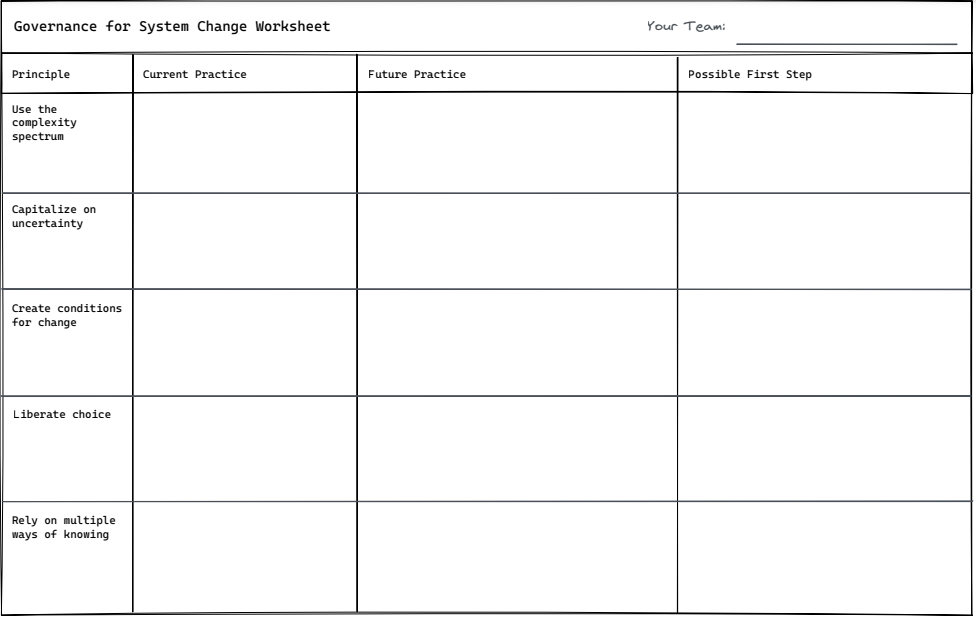

Learning to use a different frame for how we govern system change is a practice, and it takes time to develop. Devoting time to consciously changing your governance practices is the first challenge you will confront. But remember, systems seldom change on a dime, and neither do we. You might want to start with the system you know best and are closest to — you and your own organization.

One way to start is to use these governance practices as a set of prompts for your own self-reflection and experimentation, such as:

Using the Complexity Spectrum. How are we differentiating among our organization’s approaches along the Complexity Spectrum? Are we developing different mindsets and practices for clock versus cloud initiatives (e.g., solutions at scale versus system innovation or transformation)?

Capitalize on uncertainty. How are we cultivating good uncertainty and capitalizing on it? Are we resisting the urge to create certainty when there is none?

Liberate choice rather than trying to control it. Do those closer to the context feel they are able to make the choices needed to engage the system effectively? How well are our aspirations, guardrails, and learning processes helping us learn from the choices we make? What levels of trust are we able to build?

Focus on creating the conditions for change. What are the conditions that will support change in our organizational system? How well are we supporting them? How might we revise them? How are we understanding what others in the system feel are the conditions that will drive change?

Rely on multiple ways of knowing as you navigate the journey. Are we getting in touch with our own ways of knowing and cultivating openness to others? Are we trying both small and large experiments? (e.g., creating space in meetings for check-ins and reflection time? Building a more equitable evaluation practice or sitting in the tensions between different world views?)

Lastly, give yourself and those around you room and permission to change. Rather than expecting to get it right, focus on getting it better. Together I think we can do just that.

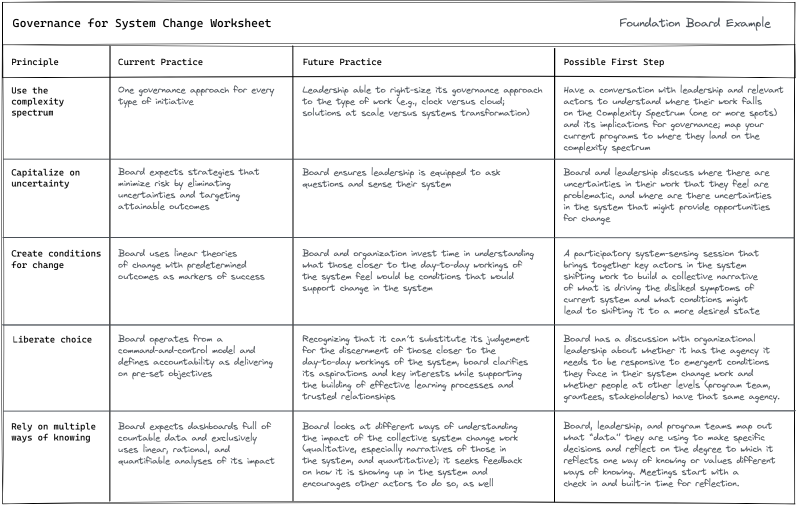

Download a PDF of the blank worksheet

Download a PDF of the example worksheet

Acknowledgement: While I take responsibility for the words used in this blog, the ideas come from dozens of colleagues, hundreds of conversations, and thousands of hours of experimenting and learning by many.

[1] I will often refer to the work of a foundation board because this is the context I know well.

[2] I am using the terms technical, adaptive, or emergent approach instead of technical, adaptive, or emergent strategy to avoid confusion with established writing on these types of strategy. There is a fair amount of commonality of usage of the terms technical, adaptive, and emergent between this piece and earlier works, but there is not 100% overlap and I want to avoid confusion or to imply that I am redefining these types of strategy. For writing on the subject, see the works of Ron Heifetz, Adrienne Marie Brown, and Henry Mintzberg.

[3] In this case, substantive outcomes mean measurable changes to the symptoms of the problem we are concerned with, as opposed to the process by which we work.

[4] This is particularly important when working with complex systems where those closest to the context need the ability to respond to what they are learning. This is what Gen. Stanley McChrystal found in doing counterinsurgency work and wrote about in his book, Team of Teams. McChrystal saw the need to empower choice from units on the ground by creating more distributed decision making.

[5] See The Power Manual by Cyndi Suarez, p. 13.

[6] See The Tyranny of Structurelessness by Jo Freeman who wrote about organizing the women’s liberation movement in the 1970s. Here is a relevant passage: “Contrary to what we would like to believe, there is no such thing as a structureless group. Any group of people of whatever nature that comes together for any length of time for any purpose will inevitably structure itself in some fashion. The structure may be flexible; it may vary over time; it may evenly or unevenly distribute tasks, power, and resources over the members of the group. But it will be formed regardless of the abilities, personalities, or intentions of the people involved.”

[7] For guidance on developing a guiding star, see the Systems Practice Workbook.

[8] Multiple Ways of Knowing: Expanding How We Know, April 27, 2017, Non-Profit Quarterly.

[9] Here is a quick description of the five minds.

[10] Here a quick explanation of the science of intuition: “Intuition is a form of knowledge that appears in consciousness without obvious deliberation. It is not magical but rather a faculty in which hunches are generated by the unconscious mind rapidly sifting through past experience and cumulative knowledge.”

Rob Ricigliano is the Systems & Complexity coach at The Omidyar Group, where he supports teams as they engage complex systems to make societal change.

originally publshed at In Too Deep

featured image by kazuend on Unsplash

Network Weaver is dedicated to offering free content to all – in support of equity, justice and transformation for all.

We appreciate your support!

Related Posts

April 22, 2025