Systems change is not for everyone, but making a good choice is

Philanthropies are increasingly becoming key players in the field of systems change. As organizations grow more innovative and risk tolerant, they are logical partners to those working to shift systems for the better.

In addition, the work many philanthropies are doing to reckon with drivers of inequities and racism — which very often contribute to their accumulation of wealth — requires many of the same changes that systems work calls for. In fact, breaking the deeper patterns that drive racism is itself a system change effort.¹

Systems change, however, requires philanthropies to operate in ways that are often unfamiliar, even counter to traditional ways of working. While we all need to see the world through a complex systems lens, systems change is not an approach that every philanthropy can responsibly pursue.

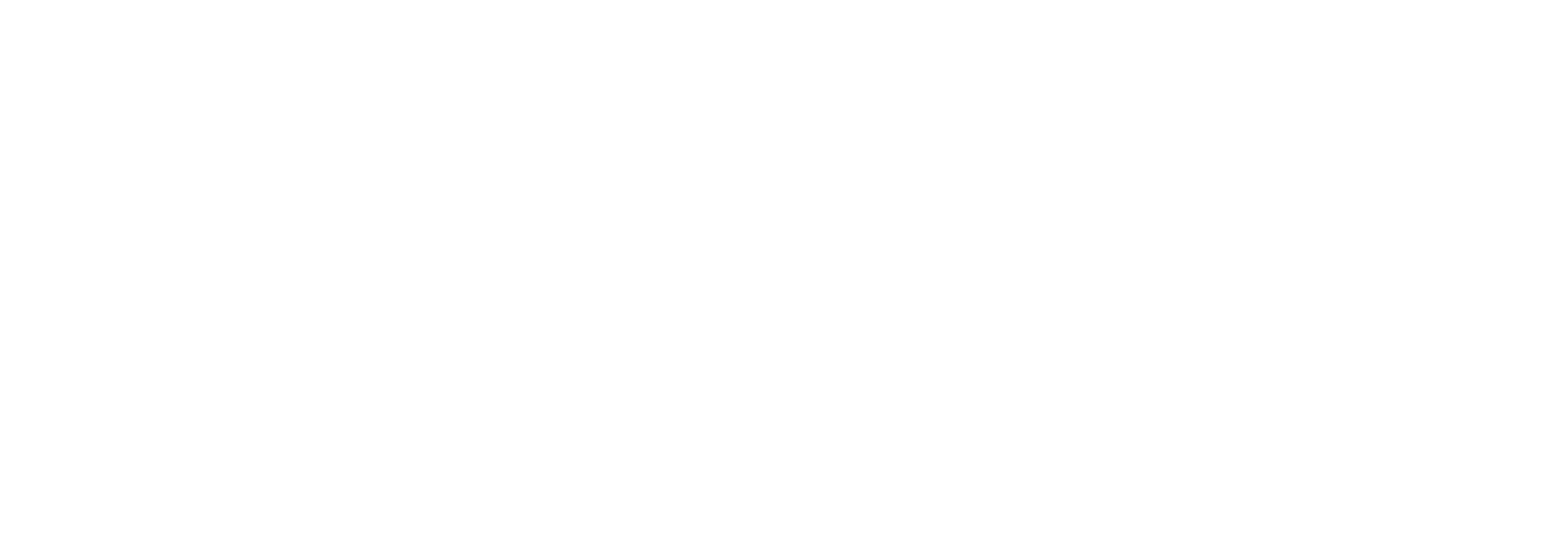

Clock vs. Cloud

Systems change is a “cloud problem” that exists in a world built for “clock solutions.”

The clock vs. cloud (or complicated vs. complex) distinction is based on the insight that most challenges lean toward two distinct types:²

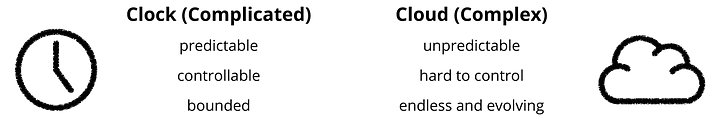

These two types of problems require two fundamentally different approaches:

Like most organizations, philanthropies traditionally focus on a clock approach: solve problems, fix what’s broken, and get it done as quickly as we can. But that’s not how systems work:

-

- -Systems don’t get solved. At best, we hope to shift systems to a healthier state.

- -Systems don’t just need things fixed. They need healing — healing of relationships, historic inequities, destructive patterns, and the environment.

- -Systems are infinite. There is no finish line that can be crossed in days or even a few years. Maintaining healthy systems is an ongoing task.

Damage can be done when we try to fix what needs to be healed or think we can solve that which is unsolvable. Rather we must apply the appropriate approach to the type of problem being addressed.

“We shouldn’t try to fix what needs healing or heal that which can be fixed.

– Dr. Failautusi (Tusi) Avegalio, University of Hawaii

Philanthropies interested in pursuing system change should avoid thinking of mission in terms of solving problems — or worse, thinking they can fix in a matter of months or even a few years that which needs healing. In contrast to a mission statement that is some form of “we exist to solve the world’s biggest problems,” systems change needs a different formulation. Something like:

As a philanthropy, we make good use of our resources to support the well-being of people, relationships, processes, and ecosystems as they grapple with complex and dynamic challenges.

Why “good use” instead of “highest and best use?”

Philanthropies often think being good stewards of their resources means putting those resources to their highest and best use. But highest and best is an impossible standard when dealing with the uncertainty and unpredictability of cloud problems. Moreover, highest and best implies an expectation of perfectionism which, while a conceivable aspiration in the clock world, can be counterproductive, even destructive in the cloud world.³

Why “support the well-being” instead of “solve problems” or “create impact?”

As outsiders, as opposed to those living in the system, a system is not our problem to solve. In cloud environments, change often takes time and has multiple influences and repercussions. Tying something you did to a specific, sustainable, and systemic impact is nearly impossible.

Why “people, relationships, processes, and eco-systems?”

These are the sources from which system change emerges. It takes a system to change a system. Lasting change is more likely to happen if those in the system, as well as their relationships with each other and with the wider environment, are healthier.

A Spectrum of Choices

The goal in exploring systems change for philanthropies is not to argue that everyone should be doing this type of work. The goal is to help philanthropies make good choices about how to use their resources (financial, people, social, network, etc.)

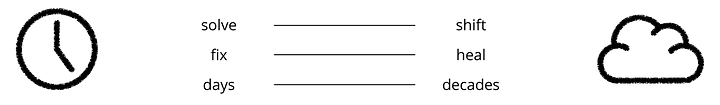

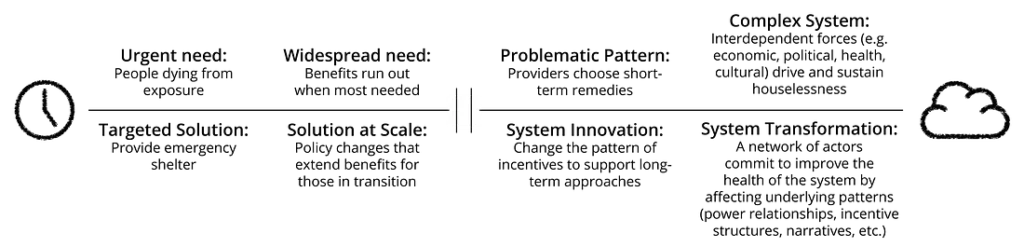

The choice of systems change is not a binary one. Rather there are distinct types of problems and interventions that exist along the spectrum from clock to cloud.

To illustrate the Complexity Spectrum, take the issue of houselessness:

The key to understanding the Complexity Spectrum is understanding differences in clock and cloud problems and approaches. The defining characteristic of a cloud approach is that it targets the underlying patterns of behavior that make up a system and drive the outcomes the system produces (e.g. underlying patterns that drive levels of poverty and make it difficult to “fix” the impacts of poverty like lower life expectancy, increased stress levels, etc.) If an approach aims to just lessen the extent of a problem or ameliorate the impacts of it, it’s more clock than cloud.

The murkiest part of the spectrum is the difference between Solution at Scale and System Innovation. This can be confusing because the same tactic can be a Solution at Scale or a System Innovation depending on how it is implemented. Take for example Housing First in Salt Lake City and Calhoun County, MI.

In Salt Lake City, Housing First was used to remedy the problem of the chronically houseless, defined as houseless people with histories of substance abuse or mental illness. As a Solution at Scale, it was effective. Chronic houselessness was cut by 90% for the target population over a ten-year period.⁴

This success was hailed as an example of how Salt Lake City had solved houselessness. But over the same period, the number of people living in houseless shelters doubled. Why? The program was designed to solve a widespread need among a portion of the city’s houseless, but it was not designed to address the many complex and interconnected forces that drive houselessness and make it difficult to emerge from.

In Calhoun County, in a project supported by noted systems change practitioner David Stroh, they asked a different question. What was keeping the network of actors in the houseless system (providers, houseless, government, advocates, community groups) from being more effective at dealing with houselessness? They found these actors were being incentivized by a variety of sources to choose short-term fixes to houselessness rather than work on the more complex reasons driving houselessness in the first place.

The key actors in the system worked collectively to interrupt the pattern of short-term incentives and create a new pattern of relationships and processes by which they would work to deal with houselessness. They too started with the Housing First program, and it was effective. But Housing First was an outcome of a System Innovation approach — it changed key relationships and patterns that drove houselessness in the County.⁵ When the Great Recession of 2008–2009 hit, levels of houselessness did not spike even as there was a major loss of jobs in the area. In this case, a key pattern in the system changed and, as a result, the problem of houselessness was also changed.

Note the type of activity can be the same in a Solution at Scale and System Innovation. The difference is that System Innovation targets a persistent pattern (the incentive structure). The choice of Housing First in Calhoun County was a result of changing that pattern. Conversely, as a Solution at Scale, Housing First in Salt Lake City was used as a direct intervention and did not aim to change the underlying patterns driving houselessness in general. In this case, Housing First succeeded at meeting the needs of a significant population, but it did not change the system itself.

So what’s the main distinction between System Innovation and System Transformation? A system has interconnected patterns that drive the system and its outcomes. A system can have any number of patterns, depending on how deep one wants to go in understanding the system. System Innovation targets one or two of these patterns and its success depends on whether changing a specific pattern is sufficient to create a sustainable, positive change in the overall system. System Transformation, on the other hand, aims at changing the system itself by changing multiple patterns as well as how those patterns affect each other. So the key difference between System Innovation and Systems Transformation is the number and extent of patterns that are being affected.

Making a Good Choice

As the houselessness example portrays, challenges have both clock and cloud dimensions and have the potential for Targeted Solutions, Solutions at Scale, System Innovation, and System Transformation. The point of the spectrum is to show us that, in every situation, we have a choice as to where and how to engage.

Systems change is not right for everyone nor is it necessary for every problem. While the renewed interest in systems change is promising, it has a downside. The popularity of systems change almost certainly means that people and organizations are choosing it when they shouldn’t. They may lack the capacity to do the work, or only do it because they feel it’s what’s expected. Or worse, they may label an initiative as systems change when it isn’t.

Making a good choice is a function of three critical ingredients:

-

- -Your Mission and Values. The expression of who you are, what you care about, and how you want to be in the world

- -Your Capacities. Skills, relationships, practices, structures, and mental models at multiple levels (individual, organizational, network)

- -Your Context. The ecosystem in which the challenges you care about exist and that affects how they may change into the future (e.g. people, structures, attitudes, narratives, trends, patterns, the natural and built environment, etc.)

Ideally, an organization aims to find the sweet spot where mission and values, context, and capacities align; a particular approach will allow you to effectively serve your mission in a specific context using your distinctive capacities.

Let’s take a hypothetical organization whose mission is to reduce houselessness in a major US city. Assume that organization takes a system-level view of what drives houselessness in their community. As noted above, they are likely to find some version of each of the four challenges (urgent needs to a complex system) and the potential for the four approaches. But assume their analysis also shows:

-

- -The system overall is moving in a positive direction and many novel and promising approaches are emerging.

- -Recent policy changes mean there are many new benefits for those in or emerging from houselessness, but there are many obstacles to applying for and receiving those benefits.

- -This “benefits gap” creates a widespread need among the houseless.

- -There is still uncertainty whether these emerging trends will continue in a positive direction and if policy changes will help, or if old patterns that drive houselessness will re-emerge.

- -There are still many houseless who will face urgent needs for shelter when the weather turns cold, and there are many chronically houseless who are still underserved.

The organization is tech savvy, has strong capacity in product development, and solid relationships with local government and houseless providers. They do not have experience in doing systems change explicitly and lack the monitoring and evaluation capacities that highly adaptive system change work requires. And because the organization found solid indicators that the “houseless system” in their community is generally moving in a positive direction, they saw less of a need for the organization to invest in some form of systems change (Innovation or Transformation).

They decide their resources would be best used in pursuit of a Solution at Scale — an app that connects houseless and providers with benefits and simplifies the application process. But they will need to monitor whether urgent needs in the system will grow and make longer-term work much harder, or whether old problematic patterns will re-emerge and potentially undermine even an effective Solution at Scale.

Governing Amidst Complexity

The Complexity Spectrum and the mission-context-capacities framework are designed to help make a hard choice a bit easier — but it is still a difficult one. Of the three variables, capacities pose the biggest challenge:

-

- -Your mission and values are in your control. While they may be ill-defined or out-of-date, you still have control over them.

- -Understanding a complex system is difficult, but it is still possible. There are a wide range of systems and complexity tools and practices for sensing systems and how to engage them.

When it comes to capacities, however, I am not aware of any organization pursuing system change that feels they have it all figured out. In fact, I’m certain they never will — because systems are dynamic, as are the capacities needed to engage systems.

Philanthropies, like most organizations, will take time to become agencies of system change. Effective governance — the ability to make a steady stream of decisions in the face of complexity and outside of just the board room — will allow philanthropies to become effective contributors to system change efforts. Governance, in service of being agile and adaptive, is the key capacity that philanthropies must develop to be effective at system change. The next blog in this series will explore this idea further.

* * *

Note on definitions: the use of the term “system” in this piece refers to an aid for learning or discovery — a helpful way to understand reality. In particular, the word system here refers to a complex adaptive system, meaning it is ever evolving and made up of many patterns of behavior that persist and change over time, and which interact with and affect each other. In this sense, system, as used here, is not a real thing; it is a mental model. A complex adaptive system, as used in this piece, is distinct from seeing just the tangible elements of a system (e.g., seeing a healthcare system as consisting of patients, providers, insurers, first responders, nurses, doctors, regulators, etc.) versus seeing the dynamic patterns that drive the level of health in a community (e.g., a poverty trap where people who are poor can’t afford sufficient healthcare; but because their health suffers, their earning potential is limited). The theory behind using the complex adaptive system is that understanding patterns of behavior and affecting them is the way to change such systems over time.

[1] See Systems Change & Deep Equity: An Interview with Sheryl Petty and Mark Leach; And the work of Jara Dean-Coffey and the Equitable Evaluation Initiative; Also Dean-Coffey, J. (2018). “What’s Race Got to Do With It? Equity and Philanthropic Evaluation Practice.” American Journal of Evaluation, 39(4), 527–542.

[2] Clock-Cloud are terms coined in the 1960’s by Karl Popper; Complicated-Complex have been described by Dave Snowden (in the Cynefin Framework) and Brenda Zimmerman.

[3] Okun, T. “white supremacy culture.”

[4] Hobbes, M. “Why Can’t America Solve Homelessness?”

[5] Stroh, D. P. (2009). “Leveraging Grantmaking: Understanding the Dynamics of Complex Social Systems.” The Foundation Review, 1(3). 109–122.

Rob Ricigliano is the Systems & Complexity coach at The Omidyar Group, where he supports teams as they engage complex systems to make societal change.

originally publshed at In Too Deep

featured image by Wolf Zimmermann on Unsplash

Network Weaver is dedicated to offering free content to all – in support of equity, justice and transformation for all.

We appreciate your support!

donate in the box above or click here