Visionary Organizing Lab began in 2016 as a volunteer based project conducting workshops on building beloved communities and a new economy.

Since we began, research across disciplines and the political spectrum has increasingly demonstrated that the global economy is reaching its systemic limits and is in terminal crisis.

Consequently, we are entering a global transition as significant as that from feudalism to capitalism. This knowledge, combined with an evaluation of our pilot, has led us to conclude that we need a consistent research program to fulfill our mission. Visionary Organizing Lab is therefore evolving into a staff based think and practice tank, conducting research on the global economy and on projects that a new system might emerge from.

We will distribute our findings through briefings, publications, short documentaries, and incorporate them into future trainings and workshops.

What do you mean the global economy is reaching its systemic limits and is in terminal crisis?

Despite the idea that globalization is new, from its inception capitalism has been a global system linking every area of the world in which it is felt. When Columbus arrived in the West Indies, he was laying the initial patters of a global economy. As the Portuguese began to trade enslaved Africans throughout the western hemisphere, these global connections and patterns were deepened. When the British, French, and Dutch began to battle for control over these patterns and connections, the connections themselves became more solid as did the place of North America in this new world. With revolutions in what became the United States and France, a form of representative democracy was born that tied these global economic patterns together politically. Creating laws that enabled economic growth on a world scale, these political relationships between nations created a way to maintain the system’s equilibrium and facilitated the growth of an entire economic and cultural system that eventually came to cover the entire world. We call this system the “modern world-system.”

As long as the world’s industrial capacities remained primarily concentrated in Europe and North America, the system had what it needed to grow and create profits. However, when industrialization spread to the global south and the global north began deindustrializing, it greatly de-ruralized the world, spreading pollution worldwide and employing what had been a cheap, rural reserve of workers.

Consequently, the supply of low wage workers needed to expand profits and the ability of firms to pollute the environment without financial and human costs have both been exhausted. As a result of these trends, we are faced with a climate crisis of epic proportions and the system is quickly reaching its limits for the further accumulation of capital and growth.

Approaching these limits, the system is in terminal crisis, increasingly unpredictable and subject to huge crises and fluctuations. As with all systems in this terminal state, opportunities exist to create a new system(s). Since launching our pilot we have come to understand this historical period as one of “systemic transition.”

What do you mean by “systemic transition?”

All historical systems have three phases:

emergence, normal functioning, and structural crisis. Capitalism emerged 400-600 years ago, functioned normally from 1648-1968, and entered its structural crisis between 1974-2008. A system enters structural crisis when, typically in response to a prior crisis, its equilibrium shifts too far from its normal center. At this point, a system is increasingly characterized by crises and chaos that can only be resolved by a new system with a new equilibrium.

This period when a system is reaching its limits and the emergence of a new system(s) with a new equilibrium is being worked out is called a systemic transition. Whether we like it or not, capitalism and the entire modern world-system is transitioning into something else because it is in structural crisis. Importantly, its transition presents an opportunity for humans to create a new system rooted in the values of love, dignity, and sustainability.

So there’s hope? How might we transition into a new, more loving economic system?

Yes, the basis of all our work is hope and a belief that the human spirit is strong and wants to grow and develop. We also believe that the willingness to assume responsibility for systemic transition is something human beings need great support to do. Most of us lack confidence, lack a sense of being powerful, and lack the ability to think in systems based ways. To transition into a new, more loving economy, human beings can and must transform these things about ourselves. Visionary Organizing Lab is committed to facilitating these transformations.

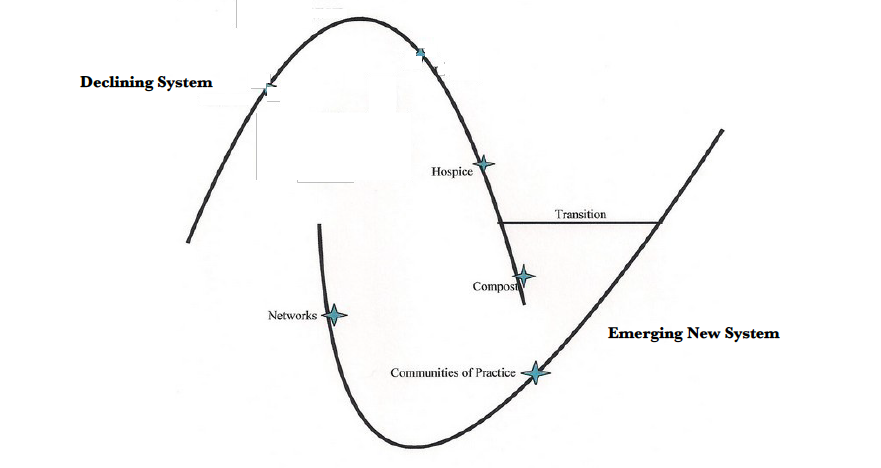

Creating a loving system will require patience, imaginative experiments, and a process of trial and error. Systems emerge very slowly, result from repeated patterns coalescing over time, and seldom emerge from a blueprint. Rooted in visionary organizing, these experimental projects must be designed to meet people’s material and spiritual needs, potentially beginning with questions like, “What effective ways for providing people with a means to sustain themselves other than wage labor might we create or already exist?” or, “What effective ways of community based problem solving already exist or might we create to eliminate the need and justification for police?”

Once experiments have some tangible results, when linked with similar projects, they can form networks of people and projects working to meet human needs absent a culture of domination. Building on these networks, a new system will require the emergence of intentional communities of practice, where knowledge about how to better meet each other’s needs absent a culture of domination can be furthered. At this second stage of a system’s emergence, developing communities of practice requires a group of people who are self-consciously committed to developing a new system.

By continuing and advancing these experiments in communities of practice, these projects can be taken to scale, and the links between them can form what Meg Wheatley and Deborah Frieze have called “systems of influence.” With evidence that this system of influence can meet people’s needs, these once experimental projects can become accepted norms. Transitioning into a new system will require bringing more people into these accepted norms and providing hospice care for the capitalist system, essentially turning it to compost. The diagram below illustrates the emergence of a new system and its relationship to a declining system:

What is Visionary Organizing and what do you mean by hospice care for the old system?

In the same why that hospice care is a means to make someone dying more comfortable, providing hospice care for the dying system involves making life more comfortable for those affected by its death. Systemic transition will be painful for everyone who experiences it. A system in structural crisis is unpredictable, chaotic, and crisis prone. When the economic system that organizes your life goes through structural crisis, life can become increasingly hard. To make that transition more comfortable, hospice care for a dying system looks like basic progressive policies for things like universal health care and guaranteed access to food, water, and shelter.

In contrast to the kind of organizing needed to provide hospice, visionary organizing is a philosophy and practice rooted in the belief that human beings have spiritual and psychological desires to grow in ways made very difficult by capitalism, racism, and patriarchy. Visionary organizing assumes that by starting with a collective vision of what a new world might look like, then working backwards to figure out what kinds of projects might make reality more closely resemble that ideal, people can collectively build a new system under which the human spirit can grow and flourish.

That sounds nice, but what does it look like?

Visionary organizing looks like living in a food desert and starting to grow food for an entire block using whatever land is available and coming to understand that practice as a potential foundation for a new economic and social system.

Visionary organizing looks like responding to police brutality not only by protest but by also creating neighborhood conflict resolution teams and practicing community based conflict resolution so that people don’t need to call the police to resolve conflicts, and seeing this practice as a potential basis for a new culture.

Visionary organizing also looks like meeting people’s economic needs through things like barter economies, alternative currencies, and community production, and seeing these practices as potential bases for a new economic system. These are just a few examples of what visionary organizing concretely looks like.

Oh, that approach makes a lot of sense. So what do you do? Why do you call yourself a lab?

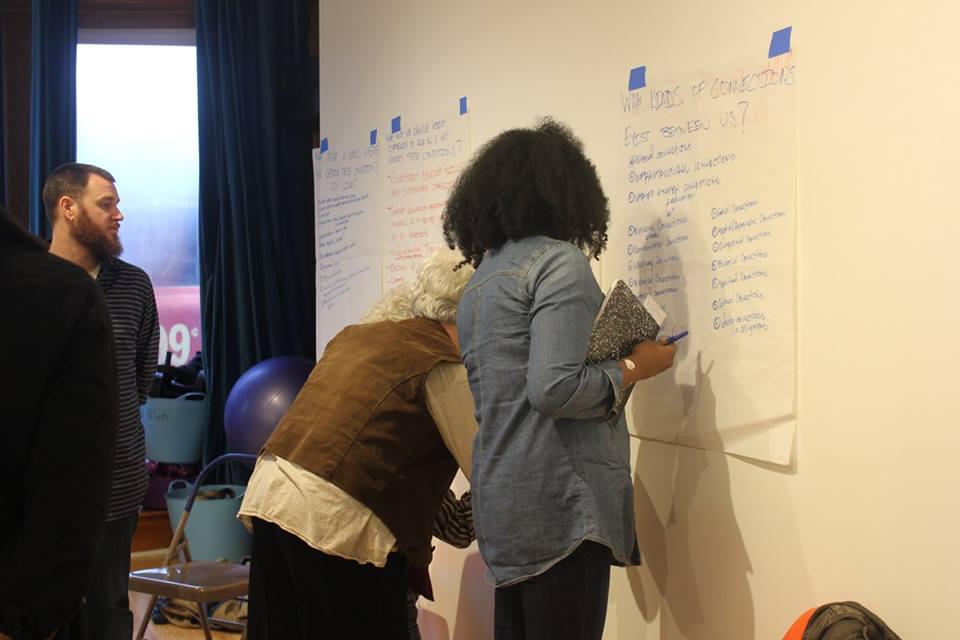

We call ourselves a lab because we experiment with ways to spread awareness of systemic transition and skills needed to facilitate it. Our primary laboratory are trainings and workshops that we call praxis labs.

In praxis labs people collectively experiment with theory, reflection, practice, and the relationship between all three. People are connected to their knowledge of the world around them, supported in understanding how who they are is connected to the larger world, and connect with how they and others might become more human human beings by experimenting with practices that can become a basis for a new system.

For example, a praxis lab on visionary organizing helped Rev. Kelly Steele from Savanah, GA, “to see that our great grandmother’s stories and landscape have direct ties with our current story and landscape,” because “the issues we face today are a direct product of Western imperialism and disconnection from the land, each other, and a sense of community.”

Corbin Leadlein, an organizer and activist from Brooklyn, NY attended four of our pilot praxis labs and came away, “from all of them having engaged in thoughtful, challenging, and inspiring discussions that have helped me to reflect on my role in creating beloved community.

The discussions are participatory, dynamic, and both focus on participants’ personal experiences while also appreciating how our stories fit within trends of historical development. I appreciate that the workshops conclude with participants coming up with tangible actions and projects that can be taken up in their respective neighborhoods and communities.”

To facilitate this learning process, praxis labs create spaces for reflection, conversation, and exchange. In praxis labs we put our reflections on everyday life in conversation with larger structural and historical phenomena. Through that conversation, we create space for people to appreciate their unique capacity to contribute to the world and come to see how personal and larger social transformations are connected.

As the above experiences show, this process creates conditions for people to imagine what we and our communities are capable of, as well as develop practices to facilitate these possibilities and understand their systemic implications.

That’s impressive. How does the research you propose compliment praxis labs?

After evaluating our 18-month pilot six points became clear:

People are excited to think through the creation of small projects to build community. It is very easy for people to see these small projects as “feel good” things that lack larger significance. When involved in the co-creation of a systemic understanding of history, people quickly understand that if small projects are networked together they can form the basis of a new system. In co-creating this systemic understanding of history, people quickly grasp that despite their feelings of powerlessness, they actually have great power to create projects and contribute to building a new system.

Despite this awareness of their creative capacity and power, imagining and coming up with actual projects within a systemic context to collectively experiment with is a major challenge for most people. Already existing filmed examples of projects can be useful for imagining visionary projects.

However, because these examples are disconnected from the systemic understanding of history co-created by praxis lab participants, they tend to undermine the kind of systems thinking developed in praxis labs and necessary for the emergence of a new system.

From these six observations, we have concluded that we can best support people in visionary organizing by incorporating examples of already existing projects into praxis labs within the systemic understanding of history co-created in praxis labs. To make our praxis labs more effective, we aim to create short documentaries and publish briefings that place visionary projects in the framework of systemic transition.

What other roles will the research, short documentaries, and publications play?

Systemic transition is a very difficult idea to grasp and accept. Our hope is that our short documentaries and briefings can make it easier to grasp, accept, facilitate, and live through. By presenting people with an easily digestible picture of the historical evolution of the modern world-system, we hope to provide people with a language to help them understand and accept the crises and transformations surrounding them.

By providing them with a story of people who have come together to build a barter economy or an alternative currency, for example, we hope to provide them with an example of something they can do with their neighbors to meet each others needs without money.

By documenting and promoting the way that participation in these projects has transformed them, we aim to provide people with hope and to support them develop an image of themselves as leaders in the creation of a new system.

We are also planning to use these materials to recruit research and activist fellows, convene conferences, and generally promote the idea of systemic transition and the possibility of a more loving economy and world-system.

This sounds like a really important project. How might I help? Can I get involved?

There are several ways you can get involved.

- You can book Visionary Organizing Lab to lead a praxis lab for your organization or volunteer to organize one in your community. We will come to any group of people that want to learn about systemic transition. Booking information can be found at: https://www.alliedmedia.org/visionary-organizing-lab/booking

- You can become a monthly sustainer of Visionary Organizing Lab or make a one-time donation at: https://www.alliedmedia.org/visionary-organizing-lab/donate

- All donations are tax-deductible and processed through our fiscal sponsor, Allied media Projects.

- You can follow us on twitter and facebook, discuss systemic transition with others, and contact us for more information.

Related Posts

September 24, 2025

Thank you & Farewell

November 4, 2024