Dense community networks bring resilience, equality and agency to our places: how we’re mapping and exploring social capital to test and develop these hypotheses

Strong communities are made up of rich and complex relational systems of feedback and support that develop over time; they have a tightly bound social fabric, woven from myriad overlapping networks of trust and reciprocity that mean they are resilient to tensions. Edges are less likely to fray, and holes are naturally tended and repaired. They are a parachute and a cushion. This is the fundamental hypothesis behind our digital mapping tool, Understory; that community is the first line of defence in a crisis, and that strong networks make them resilient. This was borne out of the realisation that communities hold the power to protect themselves in times of crisis, demonstrated so clearly by the pandemic response. This was the time when everyone truly woke up to the value of place-based social networks.¹ ² ³

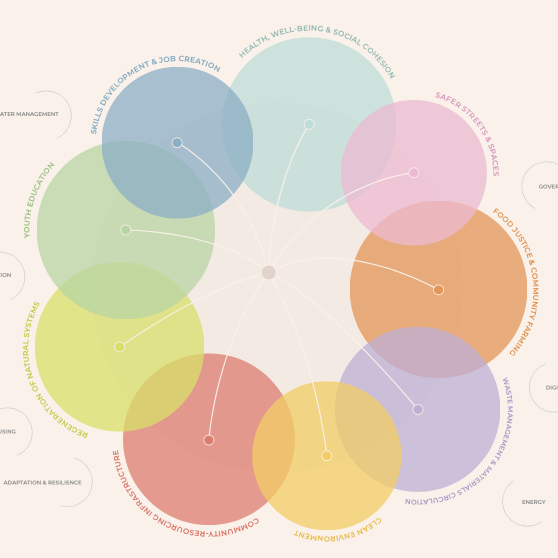

These relational networks work on a number of levels. In network analysis, we talk about the bonding, bridging and linking social capital that can exist in a place. In summary, these relate to the tight social binds that hold a like-minded group together (bonding capital), the human bridges that link different groups of people together (bridging capital) and the people or organisations who have links out of their place to sources of power (linking capital). Bonding capital is great but tribal, and can make a place siloed. Bridges (and they can be people or organisations) are fantastic — they are the glue that bind different groups together, allowing for difference and supporting plurality, democracy and efficiency. The links out to power might help bring funding or government support into a place — and if the person or group it comes in via is well bridged, that will enable that support to spread and its value to be shared.

During those early testing times of the first covid outbreak, it was well documented that the places that fared best were those that still had strong community networks in place; places like Watchet, where we’re based, and where a mutual aid group was established in a matter of days. Here, volunteers delivered shopping and medicine and walked dogs for the more vulnerable members of the community, who in turn manned the service phone lines. This whole system was set up and delivered by the community at lightning speed because the networks of trust already existed. It’s a place where shops and pubs quickly turned their hands to feeding people, delivering shopping, working cross sector to get people the help they needed. Watchet is a town brimming with bridge folk, so multiple groups were able to work together quickly and easily to ensure there were no holes in the system — that no one was left behind. And our linking capital meant that we quickly got the funding in place to support this. Those places that didn’t have this kind of social capital at play had to wait for the top-down Government-led aid to deliver that same support — but this was a system that failed to deliver despite enormous volunteer willing. Trust, it would appear, is a currency that can’t be replicated.⁴

This demonstrates the key function communities will play in the next paradigm of living; it is the power of our connections that will support us to stay with the trouble, to hold us tight and keep us safe in the face of turbulence, and to adapt collectively and creatively to the new world.

But why do some places have better social capital than others? Social infrastructure must play a part here — the places that exist that enable people to come together and build these connections.⁵ ⁶ ⁷ In Watchet, industry was a key part of this puzzle, and primarily this consisted of the mining and transportation of iron-ore to Wales and the making of paper, the latter of which only came to an end on an industrial scale in 2015. Wansbrough Papermill employed 20 percent of the town’s workforce at the time it closed, so did an enormous amount to bring people together in the town. We are also a peripheral place, far from any centres of commerce, so we have developed our own local economic resilience and care for one another. We are a place that has seen a butcher and greengrocer set up shop within the last five years, and where social action abounds. It’s a place with fewer than 5,000 residents, but well over 100 voluntary groups. And at a time when most small towns and villages have lost their pubs, Watchet still supports six, while it fought (and won) to keep our library. Each of these phenomenon supports the next — it’s the snowball effect of connection.

This is really interesting stuff and the raison d’etre for Understory. We believe that it is vital we understand social capital better, and that we find ways to build and support it, so that in turn, we can build resilience, but also develop agency so that communities can transition in the ways they determine, and in a way that brings everyone along for the ride.

Understory is a deeply wonderful and life affirming collaboration between two seemingly very different companies: Onion Collective, a group of place based social entrepreneurs and next economists from Somerset, and Free Ice Cream, a design studio dedicated to playful participation in complex systems. With the intrinsic values of joy, honesty and respect, and with the support of some amazing funders (currently The National Lottery Community Fund’s Bringing People Together programme) and 30 generous and brave communities up and down the UK, we’ve been exploring what this all means and how it can work — to give places the self-knowledge they need to build their own strength. It has been designed as a participatory action learning tool, so that the power resides with the communities, and is not extracted from them.

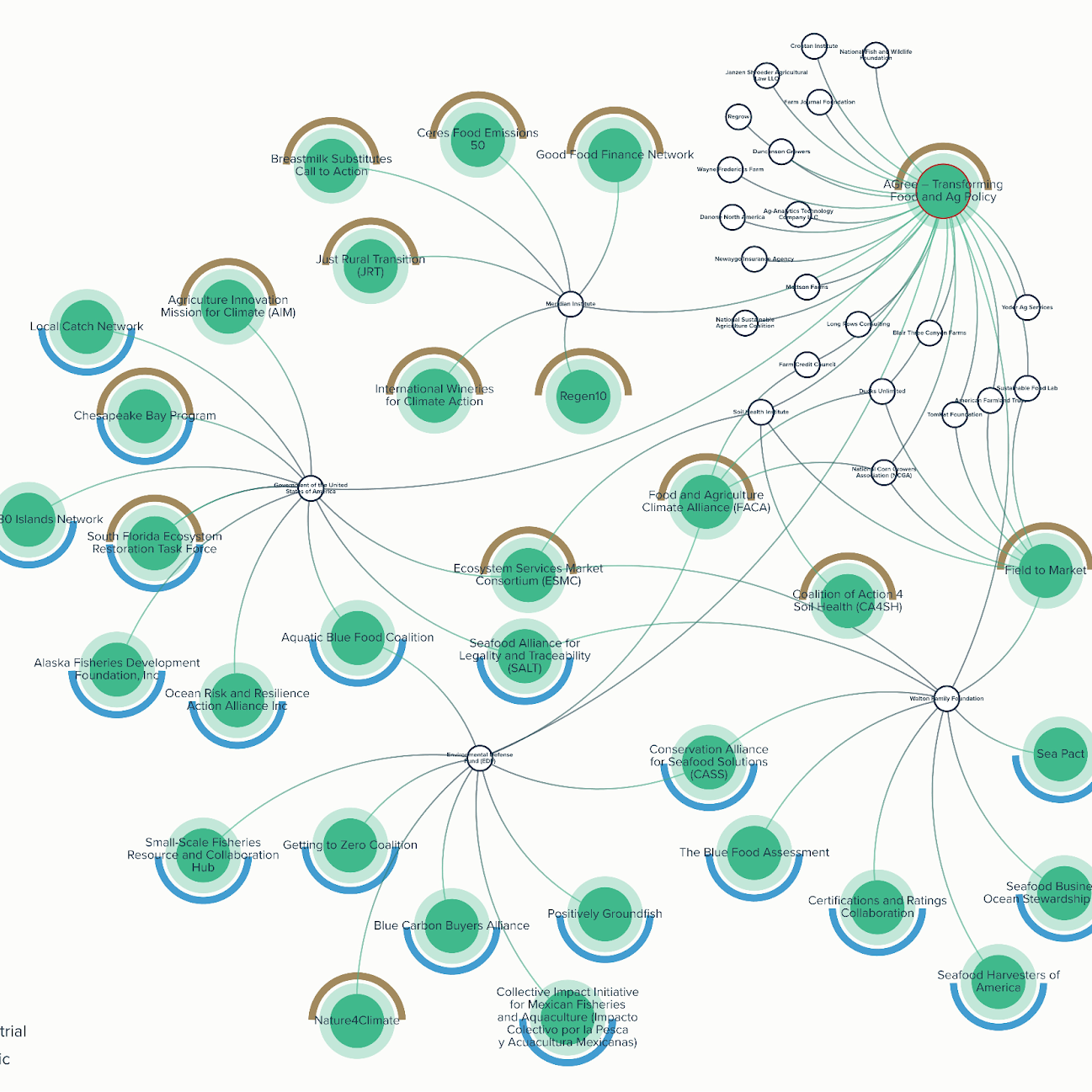

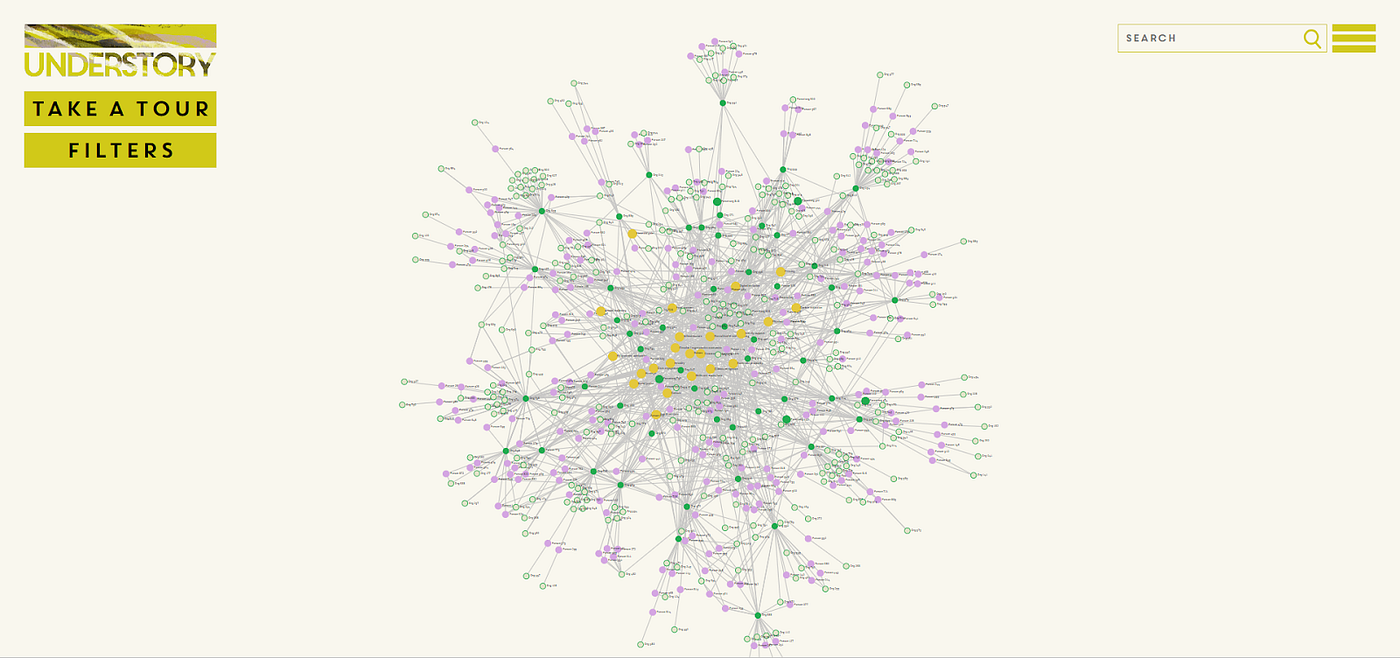

In summary, Understory works by bringing community actors together (those involved in civic action, from pub landlords to council officers to school governors to community gardeners) in a Zoom. Then, during a 90 minute session, they are asked a series of questions that serve to create a network node map in real time, which starts to depict the different types of social capital at play in their place. It also shows the purpose and sector of each of the organisations that are taking part in mapping. Those who are named in the mapping process are then invited to take part as well, which means the map expands until it forms its natural edge, based on relationships rather than geography or services, as defined by its community. Shared community ownership of this process and the data that it depicts is essential.

This segues nicely to our second fundamental hypothesis, which is that to build strength in a place, you need representation from all corners; that plurality and diversity act as an antidote to privilege and elitism, and that when different groups of people work together, they learn to understand each other’s viewpoints, and value each other’s contributions. By working together, we can begin to build bridges where we increasingly see division.

A rich web of connection naturally supports plurality by drawing people in from the edges of a place — and by mapping this, we can see where those edges are, in a community’s self-defined network map. We can also see where its vulnerabilities lie — where there are groups who are only weakly connected to the rest of the place, or if there are silos of action, or if there are a small number of individuals acting as super-connectors. Part of building resilience must also depend on this spread of social capital reaching the corners of a place. It’s no good if all the social capital is bound up in small pockets. There are countless examples of places where a few wonderful people do all the work (and so hold all the power), and we need to find ways to diffuse that. Partly because this kind of capital is vulnerable — if those people go, then so does the connection and a place loses its ability to protect itself. But also, power hoarding, however well intentioned, will mean that one group’s prejudices can become the sole narrative of a place. Strengthening bridging capital should help dissipate the hidden prejudices that exist within the network, and increase agency, by spreading the sense that we all have a role to play in our places, and that involvement in civic action can and does create change. If you want that change to reflect your own vision of the future, then there are easy and supportive routes in.

An important area of the mapping is around organisational purpose: the mapping process asks participants about their objectives, and in doing so, has the potential to support collaboration across difference. A football club and an art centre may both be working towards youth engagement and aspirations, for example, but never have thought to work together. The map will enable a place to see and then explore the rich diversity of people and organisations who are all working towards similar end goals and a more positive civic future. In this way, it can act as a springboard to action, supporting residents to distribute power and strengthen networks via common goals. If we want new ideas, the thinking goes, we need to ask new people. Fresh people and fresh collaborations = fresh perspectives and fresh action. New people also bring new energy, and increased efficiency, as groups share their resources via new bridges, and trust, hope and belief start to flourish.

There is also a more intrinsic value in connection. In Connected, the amazing power of social networks and how they shape our lives, Dr Nicholas Christaskis and Dr James Fowler explore how emotions spread. Their research shows that if you are directly connected to a person who is lonely, then you are more likely to be lonely yourself — 52% more. They also found that, “looking beyond these direct connections…. Loneliness spreads three degrees… A person’s happiness depends not only on his friends’ loneliness, but also his friends’ friends’ and his friends’ friends’ friends’ loneliness” — with the impact decreasing by around half with each degree of separation. “If we are concerned about combatting the feeling of loneliness in our society,” they conclude, “we should aggressively target the people at the periphery with interventions to repair their social networks. By helping them, we can create a protective barrier against loneliness that will keep the whole network from unravelling.”⁸ This extraordinary work shows us that it isn’t just an altruistic good to help those at the edges, that value is paid back through the network.

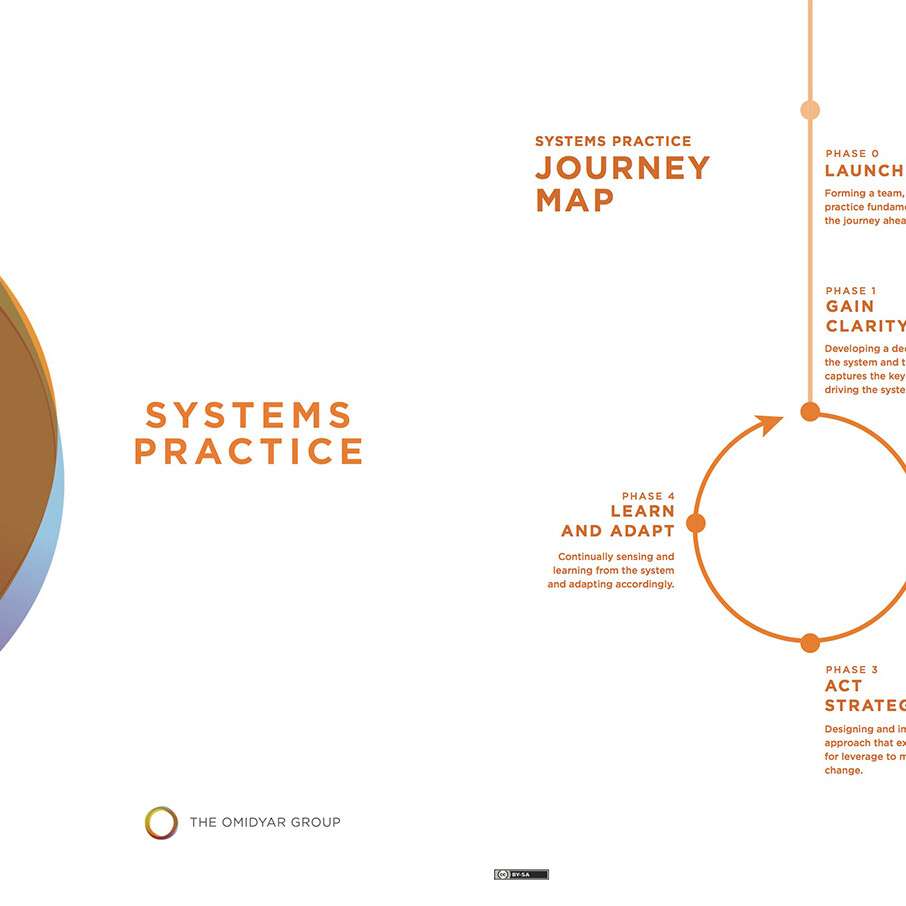

And this leads to our third core hypothesis; that self-knowledge in a place is a necessary precursor for action, and naturally promotes agency. Just like a gardener must stand back and understand the conditions of their garden before planting — the light, the plants, the soil, the fauna, the interplay; a community actor must understand their networks if they hope to tend and strengthen them, or to plant new ideas and actions. And in seeing and understanding the relationships at play in their place, they are naturally inclined to develop it further. In this way, communities can start to ask questions of themselves and decide how they want to respond to this self-knowledge. By interrogating the patterns of relationships that are at play, a community can reflect on its current position and plan for and own its own development — it can see where it is working well, aspects that are more vulnerable and places where strength can be easily built.

Metaphors abound in this work, but there’s a fairly obvious analogy between community and the soil; the rich but hidden mycelial network that exists beneath our feet, supporting the flow of resources and immunity between its different companion plants. In a forest, mother trees (the biggest and oldest trees) are the most connected. This enables them to share more of their resources throughout the forest and support the other trees and flora to withstand stress — they do this via their fungal networks. These mother trees enhance regeneration, support biodiversity, and conserve carbon storage.⁹ Similarly, if the super connectors in a place can share their knowledge and energy with others via their networks, the whole community benefits. This is how we can begin to build a better world.

This journey of self-reflection and self-knowledge are essential if communities want to work together to share power and resources, build better systems and create the future they want to be part of.

Examples of flourishing places, where ideas and action abound, can be found all over the country, and we believe these are the places with the strong connections in place. Places like Hastings, which we mapped in our first iteration of the map, which showed enormous amounts of bridging capital between different organisations. Networking together is not only efficient, but it enables new ideas to develop. Hastings is a really good example of a place that is emerging from the ashes of the current capitalist paradigm and propelling us into the next economy. It is a trailblazer in terms of community owned and driven change; a place that is keen to learn from others (see the Hastings Common Treasury of Ideas¹⁰) and has multiple examples of community led projects happening on the ground that generate real change. Hastings, like Watchet, is also coastal, and peripheral to the market economy. It’s a place that’s built up its own resilience, and where there are some clear ‘mother trees’ who, instead of hoarding power, have worked hard to share and build agency through their networks.

Strong communities like this are better equipped to imagine different stories for themselves; new community owned narratives that they can fight for. This is imperative now after decades of lost action in the face of climate breakdown. We believe that connection engenders energy and ambition, and enables people to work together to build that better world. We believe that connection also nourishes empathy and respect, and so plurality and diversity naturally follow. With this, we can build healthier, happier places, and think creatively about a new world of possibility. And when the tough times come, it will catch us, bring us together, and hold us.

To learn more about Understory, visit understory.community or email [email protected]. You can also follow us on Twitter @_understory_

Sally Lowndes is Director in charge of sustainability at Onion Collective CIC, and co-founder of Understory.

Sally joined Onion Collective in 2016, and leads on all areas of sustainability. She holds an MSc in Sustainable Development – with a focus on community – from the University of Exeter, and has worked across the environment sector, from waste journalism to sustainable food marketing, meanwhile spending years volunteering across various community projects, from food hubs to gardening projects.

Onion Collective is a social enterprise working to tackle social, cultural and environmental injustice in our hometown of Watchet, while fighting for a brighter, distributed and attached economic future across the UK. We deliver wide-reaching and ambitious regeneration projects that are holistic in nature, benefiting people and planet. Locally, we aim to create purposeful and interesting jobs, build local economic resilience, widen cultural engagement and enhance aspiration. With a macro lens, we are showcasing what is possible when you put belonging, connection and hope at the fore.

Free Ice Cream is a design studio that uses playful design methodologies to make existing structures visible, help people ask better questions of them, and imagine alternatives. To do this they specialise in the participatory mapping and playing of complex systems, and creating the conditions to imagine alternative futures and infrastructures. They also work with activists, campaigners, civil society and academia to influence policy.

References

¹ Haldane, A, Reweaving the social fabric after the crisis, Financial Times, 2020, https://www.ft.com/content/fbb1ef1c-7ff8-11ea-b0fb-13524ae1056b

² Makridis et al, How social capital helps communities weather the COVID-19 pandemic, Plos One, 2021,https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC7846018/ Research from America that shows ‘moving a county from the 25th to the 75th percentile of the distribution of social capital would lead to a 18% and 5.7% decline in the cumulative number of infections and deaths, as well as suggestive evidence of a lower spread of the virus.’ The authors surmise that because ‘social capital is associated with greater trust and relationships within a community, it could endow individuals with a greater concern for others, thereby leading to more hygienic practices and social distancing.’

³ Hall, R, Four in 10 pandemic era mutual aid groups still active, UK data suggests, The Guardian, 2022,https://www.theguardian.com/business/2022/jun/13/four-in-10-pandemic-era-mutual-aid-groups-still-active-uk-data-suggests ‘Four in 10 of the mutual aid groups that were set up at the start of the pandemic to make it easier for neighbours to help each other are still active and many have become established charities helping local people cope with the cost of living crisis, analysis suggests.’

⁴ Tiratelli, L. and Kaye, S, Communities vs Coronavirus, New Local, 2020,http://newlocal.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2020/12/Communities-vs-Coronavirus_New-Local.pdf: A key finding here was that ‘Central government has struggled to connect with Mutual Aid groups — a small scale is key: These groups operate on a hyper-local basis, and so they require local coordination and locally-specific support.’

⁵ Local Trust, Policy spotlight 1: How social infrastructure improves outcomes , 2023, https://localtrust.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2023/01/Local-Trust-policy-spotlight-social-infrastructure-2023.pdf

⁶ The British Academy and Power To Change, Space for Community, Strengthening our Social Infrastructure, 2023,https://www.thebritishacademy.ac.uk/publications/space-for-community-strengthening-our-social-infrastructure

⁷ Eric Klinenberg, Palaces for the People, Vintage, 2020

⁸ Christaskis and Fowler, Connected, the amazing power of social networks and how they shape our lives, Harper Press, 2011, pp 52–53

⁹ https://mothertreeproject.org/about-mother-trees-in-the-forest

¹⁰ https://www.commontreasury.org.uk

originally published at OnionCollective

Network Weaver is dedicated to offering free content to all – in support of equity, justice and transformation for all.

We appreciate your support!