FROM COLLECTIVE ORGANIZING TO BUILDING BLACK FUTURES

Every second Thursday of the month, Network Weavers Yasmin Yonis, Kiara Nagel and Marie DeMange host a Community of Practice conversation on Zoom. The skill-building space is available for network weavers who want to create connections and to explore questions central to their roles as facilitators, consultants and movement builders.

In March, the Community of Practice session was dedicated to unearthing what the Black Radical Tradition can teach us about how communities are self-organizing under crisis. Digital Strategist, social entrepreneur, and faith-based organizer Jayme Wooten and former organizer and founding member of Black Lives Matter Global Kei Williams, led the session through a riveting presentation that highlighted how network weaving in movement building creates strong, sustainable, and participatory avenues of community engagement.

In this first installation, I’ll be exploring some of the ideas that resonated with me from Jamye Wooten’s presentation. Join us next week for a second blog post on Kei William’s reflections on the difference between a riot and a rebellion, identifying key moments in a movement and power mapping.

What Moves You to Organize?

One of my key takeaways from the conversation was a question Jamye offered up to the group early on: “How do we move beyond react-ivism to a framework that is more wholesome and holistic?” When I think of activism, I think of forward movement, critical response to urgent community needs. What Jamey’s question opened up for me was an opportunity re-examine the impulse to act. Activism often comes out of a reaction to a perceived injustice. That reaction while visceral and binding, while it galvanizes communities towards action also depends on the viscerality of a trauma response for endurance.

Some good questions to ask in community:

Where in our organizing have we mistaken “react-ivism” for “activism”?

What can we offer as a community in its stead?

Is there room in our reaction to great harm for quietude and spaciousness so that we can recover and organize alongside our comrades?

What Kind of Network Makes a Movement?

A robust and inter-related one.

Another great offering from Jamye was an invitation to look closer at the parallels between movement building and Network Weaving. While people might remember Martin Luther King or Phillip Randolph as leaders of the Civil Rights Movement, what made the movement successful were core members like Ella Baker who helped local leaders in southern communities activate talented and capable young folks to self-organize. [1]

At the core of every network is a relationship, Jamye offers, and crucial to that relationship is trust. We often overlook the importance of relationship and trust building in the health and longevity of networks in an effort to make sure more work gets done, and yet, a sustained, years-long trust-building effort is the only way Baker’s could have galvanized as large and loose a coalition throughout the South as she did.

To that end, it’s important to know what each network needs to be able to organize resources to ensure its success. For example, an Action Network is just a collection or clustering of people who are interested in executing similar tasks: fundraising for an event or creating a mutual aid pod. What an Action Network needs to thrive might be different from a Support Network which is likely the comms and evaluations core of any successful self-organizing pod. That being said, a good Action Network is nothing without a robust Support Network, a collection of folks willing to build out systems and stay on top of resources. And a robust Support Network relies on the trust building, collaboration and thoughtful strategies that come out of relationships in intentional networks. Networks are not so much separate pods with a shared core as they are a spider

Are you using a Centralized vs. Decentralized Models?

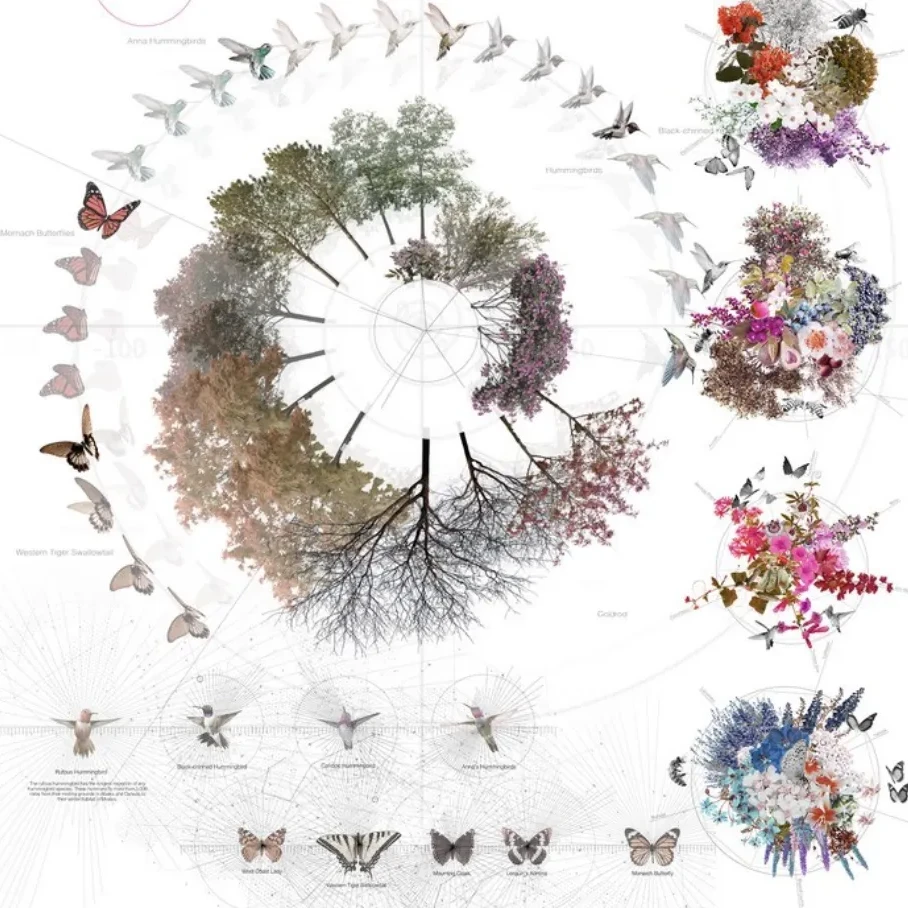

According to Jamye’s research, successful Networks are not so much spidery pods with a powerful core as they are a starfish with deeply interconnected and communicative limbs. Thinking of the limbs of the Starfish as replicable and healthy parts of a network allow us to see the importance of each part: Circles, The Catalyst, Ideology, Pre-existing Network, The Champion. A healthy network needs all of these parts to be aligned in vision, communication, interlocking values and principles so that they can adequately organize for power.

A great example of such a model in practice are the hashtag based campaigns such as #BMoreUnited in response to the spotlight on Baltimore in the aftermath of Freddie Grey’s shooting at the hands of Baltimore Police. What emerged was a coalition of citizens who operated as a network without any real leadership structure to demand justice and accountability for police shootings in their community. They were able to do so by prioritizing participatory democracy and building out a skills bank to utilize the human and financial resources that came pouring in after the media spotlight.

From Collective Organizing to Building Black Futures

The last and arguably coolest lessons from the session is that it’s possible to use digital spaces to ethically organize on behalf of communities in ways that are participatory and rigorously innovative. Take CLLCTIVLY “a place-based social change ecosystem using an asset-based framework to focus on racial equity, narrative change, and social connectedness.” The most remarkable aspects of CLLCTIVLY: its asset map/directory which aims to amplify and connect community members with multimedia projects, a strategic partnership/marketplace, a social impact institute, and a rotating Black Futures Micro-Grant . Using the seven principles of Kwanza, CLLCTIVELY aims to put old money in service of new values. COLLECTIVELY- create ecosystem to foster collaboration.

Resources:

- Old Money, New Money 2019: A Community of Practice in Three Parts

- Ella Baker and the Black Freedom Movement: A Radical Democratic Vision by Barbara Ransby

[1]https://time.com/4633460/mlk-day-ella-baker/

About the author:

Sadia Hassan is a facilitator and network weaver who has enjoyed helping organizations use a human-centered design approach to think through inclusive, equitable, and participatory processes for capacity building.

She is especially adept at facilitating conversations around race, power, and sexual violence using storytelling practice as a means of community engagement and strategy building.

She is an MFA candidate in Poetry at the University of Mississippi and has a Bachelor’s degree in African/African-American Studies from Dartmouth College.

Related Posts

October 20, 2025

Signals from the Web

September 9, 2025